Meet the Beetles!

by Robert Wyatt

One of the most famous quotes regarding biological diversity (and theology) is that of the eminent British population geneticist J. B. S. Haldane, who was asked (in some versions of the story, by wags in a London pub) what could be inferred about the Creator from study of the natural world. His response: "an inordinate fondness for beetles."

Indeed, the high diversity of beetles (Order Coleoptera) stands out as extreme, with some 350,000 species described, making them the largest group of animals on Earth. Some estimates range even higher, exceeding 1.5 million! . In the United States alone there are more than 30,000 species.

As boys growing up in North Carolina, my friends and I had a favorite nighttime activity in the summer: searching for and catching large beetles. We regularly patrolled parking lots at local shopping centers that had unshielded bright lights atop tall poles. We also searched with great success at public playgrounds with lighted tennis courts or ball fields.

Among the most prized specimens were the Eastern Hercules Beetle, Green June Beetle, Stag Beetle, and Rhinoceros Beetle. Having no proper nets or other entomological supplies, we did our catching using hands and jelly jars. Without realizing it, we were setting ourselves up well for later science classes that required an insect collection.

But all of this is to lead up to a recent discovery of a beetle that I had never seen before: the Eastern Eyed Elater (or Click Beetle). This beauty happened to land on my hummingbird feeder on 30 May 2021. At first I was dismayed because I initially thought what I was looking at, from a distance, was a dead juvenile Ruby-throated Hummingbird.

But all of this is to lead up to a recent discovery of a beetle that I had never seen before: the Eastern Eyed Elater (or Click Beetle). This beauty happened to land on my hummingbird feeder on 30 May 2021. At first I was dismayed because I initially thought what I was looking at, from a distance, was a dead juvenile Ruby-throated Hummingbird.

As I got closer, I realized that it was a very large (about 40 mm long) beetle.

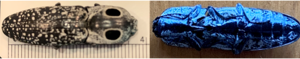

Alaus oculatus (Elateridae) is black but is dotted with silvery white scales, which are arranged on the thorax so as to delimit two large, dark "eyes." These eyespots presumably confuse or frighten potential predators. (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alaus_oculatus)

As a secondary deterrent, like all click beetles, A. oculatus can suddenly catapult itself out of danger by snapping its back and shooting into the air. Here is a link to a video showing clicking and flipping:

The larvae of click beetles are known as "wireworms," and some are serious pests of agricultural crops. But the larvae of A. oculatus are predatory on other beetle larvae, especially Cerambycidae, and have been documented in cage experiments to consume more than 200 cerambycid larvae each! Adults are said to not eat much, but their diet consists of nectar and plant juices. So maybe that's how it ended up lying on my hummingbird feeder hoping for a drink of sugar water.

The larvae of click beetles are known as "wireworms," and some are serious pests of agricultural crops. But the larvae of A. oculatus are predatory on other beetle larvae, especially Cerambycidae, and have been documented in cage experiments to consume more than 200 cerambycid larvae each! Adults are said to not eat much, but their diet consists of nectar and plant juices. So maybe that's how it ended up lying on my hummingbird feeder hoping for a drink of sugar water.

I held my visitor (in a jelly jar!) for a few hours to observe its activity and feel and hear the click. Supposedly, when placed on its back, the beetle should immediately click to right itself. But my beetle instead "played dead," drawing in its legs and antennae and remaining still. For some reason clicking would occur when simply held in my (predatory?) hand.

Dr. Robert Wyatt obtained his bachelor’s degree from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and his doctorate from Duke University, both in Botany with a minor in Zoology. He spent most of his career at the University of Georgia, where he was a Professor of Botany and Ecology for more than 20 years. He has served on the Board of the Friends of the Georgia Museum of Natural History for more than 15 years, including five as President.