The Georgia Museum of Natural History has a long, rich history dating back to the founding of UGA. Professors over the years bought and collected materials, oddities, and artifacts for their classes since the university itself didn’t have enough funding to provide those professors with classroom materials as part of the budget, which eventually culminated into respectably sized collections owned and curated by the various departments by the end of the 19th century.

In 1897, Science Hall, the first new building constructed in over a decade, was completed, on the site where Terrell Hall stands today. This building housed the Chemistry and Biology Departments (as well as administration), which also meant that it housed those departments’ collections along with it, including Chemistry’s Industrial Museum (which had over 3000 mechanical and industrial gadgets, such as an early steam engine), the Geological and Mineralogical Collection (which had been curated by the Chemistry Department head, Prof. H. C. White, since the geology professor had retired in 1892 and hadn’t yet been replaced), and the Biological Collections. While the Geological Collections were unceremoniously shoved into a closed in the basement, the Biological Collections, at least, began to thrive: in June 1901, an article from The Weekly Banner, an Athens newspaper, described a new Biological Museum which the Biology Department had begun in Science Hall: “This is a feature of recent addition to the University and new specimens are being added from year to year. Already a splendid collection is on hand, and this department furnishes not only many benefits for the student, but is also an interesting spot for visitors.” Unfortunately, a fire burned Science Hall to the ground on November 17, 1903, and practically everything from the collections were lost.

Thus began a period of rebuilding. Professor White explicitly stated in the 1904 Chemistry Annual Report that his focus was to rebuild the Chemistry Department and its apparatus, and set Geology on the back burner. Thus, the Geological Collection would be sorely neglected until the Geology Department would be re-established in 1937. The Biological Collections were actually restored rather quickly, though. Even though the Board of Trustees granted very little money to the department, the Biology professor, Dr. John P. Campbell, managed to secure several donations of specimens from institutions across the country, including the Smithsonian Museum of Natural History, to replenish the collections.

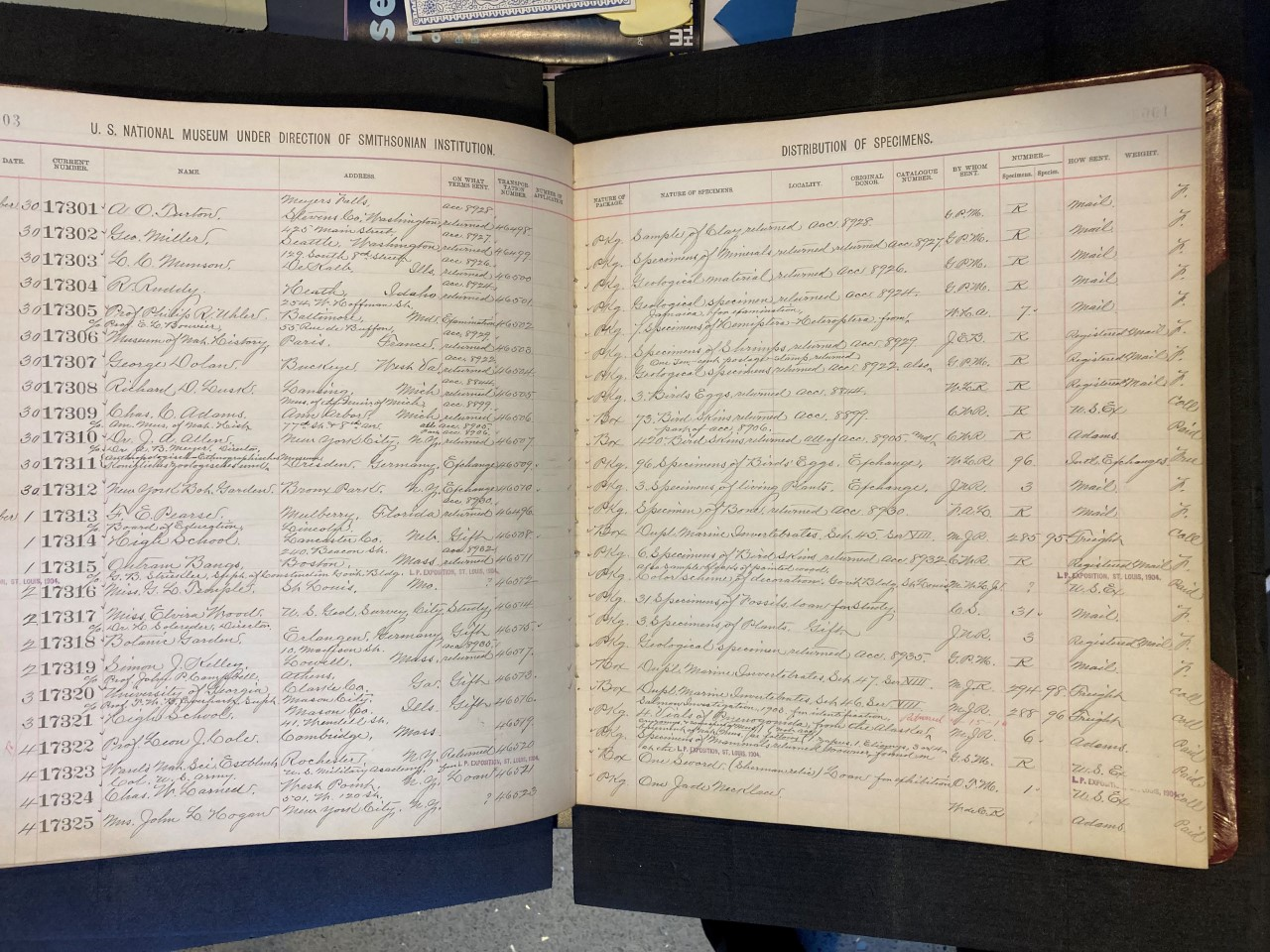

Records from the Smithsonian Museum of Natural History show that the Museum sent 294 specimens, representing 98 species, of marine invertebrates to Dr. Campbell on December 3, 1903. (Distribution #17320.) Photo courtesy of Tad Bennicoff, Smithsonian Archives.

Additionally, Botany was created as a department separate from Biology in 1908, and the first professor, J. M. Reade, was adamant about greatly expanding the Botany Collection. Under Reade’s near twenty year tenure as head of Botany, the department would eventually establish a greenhouse, a respectable herbarium, and come to offer an array of courses with ever growing student interest. In 1911, Biology (which now primarily curated the zoological collection) managed to acquire the infamous Hoxie Collection from renowned ornithologist Walter John Hoxie of Savannah, GA for $500 (or, nearly $16,000 today). This collection was composed of species of ducks and other birds native to Coastal Georgia. The purchase actually garnered national attention in the academic world. However, Biology would not receive funding to care properly for these specimens, and a number of them would decay and be lost in the next two decades.

Funding lacked to hire curators of these collections, and the professors had a hard time caring for them while also trying to perform their regular duties. Funds for the University were tight because of massive inflation since 1912 and the subsequent outbreak of World War I. In 1920, J. M. Reade, Professor of Botany, wrote in the annual report, “The museum should be considered separately from the schools of botany and zoology. It is too much to be cared for by the professors and too much to be sustained out of maintenance funds…The zoological materials in the museum are not being cared for. Dr. Campbell (now deceased) could not and did not undertake it. The result has been a considerable loss. A number of wax models have gone to pieces. A collection of Georgia birds which you purchased a few years ago is going to pieces. Several of the specimens have fallen from their mountings. Since purchase, the whole collection has stood exposed to dust and the ravages of insects…” Indeed, every department would be short on funds until the mid-1940s. Though the State did provide increased funding in these years, the true accrue of funds came from the three thousand World War II veterans who enrolled as out-of-state residents (who thus paid higher tuition and fees) from the federal government’s G.I. Bill. The Chancellor’s Office estimated that they would account for an increase in funding of nearly $990,000, which meant that, for the first time in decades, departments actually had more than enough money to operate, and were even able to expand. Botany spent over $11,000 on a new greenhouse, and in 1949, added 7,000 specimens to the herbarium, totaling 34,436 specimens (i.e. they managed to procure 20% of the collection in that year alone), and another 9,850 specimens would be added in 1950. Eugene P. Odum, a Professor of Zoology at this time, began accumulating the first true foundations of the Ornithology Collection.

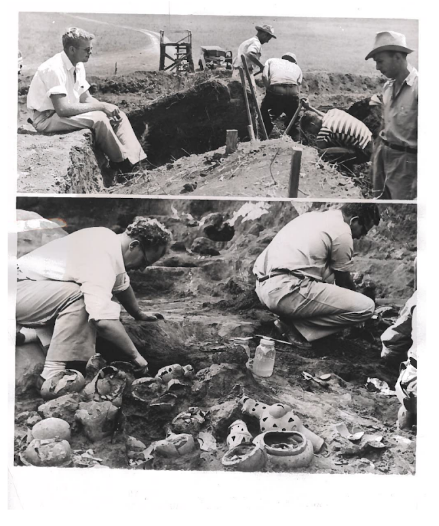

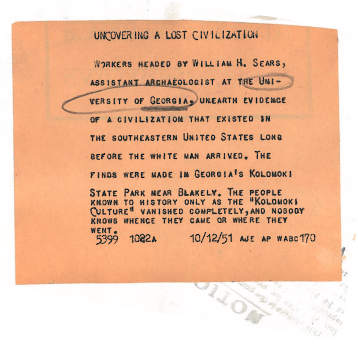

The Department of Anthropology and Archaeology briefly appeared towards the end of the 1930’s but dissolved during World War II when the professor, Dr. Robert Waucope, resigned; however, it was finally firmly established in 1947 under a new head, Dr. Arthur R. Kelly. L. L. Hendren, Dean of Franklin College, aptly stated, “It is peculiarly fitting that there should be such a department at the University of Georgia because our state is richer than any other state east of the Mississippi River in archaeological remains.” No courses were offered the first year and a half after its inception, as Kelly and another professor hired, William Sears, were busy out in the field surveying and excavating for nearly the entire time. During this period, it is important to note that Georgia was experiencing an industrial boom of sorts, and major projects– construction of highways, dams, bridges, and other major improvements in infrastructure– were popping up all over the state. These projects, however, threatened to damage or completely destroy a multitude of unprotected historical sites– hence, the resulting flood of urgent requests for UGA’s new Archaeology Department to survey and excavate these sites before the artifacts were lost forever. An archaeological laboratory was set up in the basement of Old College, where artifacts excavated or acquired by the department could be processed and prepared for museum exhibition. The department’s first official exhibit, on Muskogean Art and Symbolism, went on display in “an alcove of the Georgia Art Museum” on May 25, 1949; it would last through January before being rotated out. Anthropology would come to boast the largest collection of the Georgia Museum of Natural History, today containing over three million specimens and artifacts from Georgia and the Southeast, spanning 12,000 years of human history. Kelly would retire in 1967.

Photo and caption depict UGA professor William Sears leading excavations at Kolomoki Mounds State Park, Blakely, GA, 1951. Photos Courtesy of Hargrett Rare Book and Manuscript Library, UGA Libraries.

The first half of the twentieth century marked tumultuous times for the Museum and its collections– of rise and fall, hope and disappointment, growth and loss– which would continue to define nearly its entire existence. Nevertheless, time marched on, and the Museum survived every blow Circumstance tried to test it with, returning a little stronger, a little larger, a little tougher each time. If nothing else can be said of the museum– of the professors that spent their lives nurturing its collections, of the departments, struggling to stay afloat as they did, yet still managing to build the collections each year– it should be stated that their resiliency is astounding, and that resiliency should be commended. The Museum continues its struggles today, fighting for funding, for support, for recognition, however, the History of the Museum, long and rich as it is, with times in light and dark, has always proudly proclaimed one thing– that the future is always brighter, and the best is yet to come.